Check out or latest addition to the product line-up: CYBREI Cranks and components!

The speed you can achieve on a bicycle, or any ground vehicle for that matter, is largely dependent on the overall drag force it has to overcome, and the amount of power it can generate for its propulsion. The main components of this drag force are:

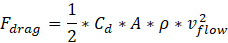

This relationship is best characterised by the following equation:

From the moment you push on the pedals and start moving, you are beginning to displace air molecules from their location, creating a high-pressure area on the leading edge of your bike, body and all of the components. This creates a pocket of low-pressure air on the trailing edge, which essentially pulls the whole system towards it, creating a drag force. This phenomenon is most commonly described as pressure drag, which is responsible for the largest portion of the aerodynamic drag. The shape of the object and the flow conditions dictate the point, at which the airflow can no longer stay attached to the object. The placement of this flow separation determines the size of the low-pressure wake and thus the drag. Streamlined objects are shaped in a way that minimises the possibility of flow separations.

Skin drag is caused by the air molecules located in close proximity of the surface of objects travelling through air, that are essentially stuck to it and move with a very slow velocity. This a lower portion of the overall drag, but it greatly influences airflow, particularly around non-air foil shapes, so called bluff bodies. In cycling, and aerodynamic clothing in particular, this effect is often used to reduce drag, as the limbs and torso of the rider are perfect examples of bluff bodies.

As it is hard to separate these two components in practice, for calculations we use an equation where the effects are summarised and simplified:

, coefficient of drag is a dimensionless quantity, that describes and summarises how the object interacts with the airflow. It has to be determined experimentally and it varies widely between different shapes of objects.

frontal area, is the right-angle projection of the object in a direction that is perpendicular to the direction of travel. The unit of measurement is m2, meter squared.

In cycling applications, it is difficult to separate these two factors, as the system of rider + bike is not a static, closed surface with a constant area, so a bundled term CdA is used.

rho, is the density of the liquid (=air) in which the object is travelling. This is influenced by the weather conditions, mainly the temperature and the air pressure.

flow velocity – it is important to note that the drag force is a function of this quantity, rather than the ground speed that the cyclist perceives. The difference is caused by windspeed and wind direction, so in result the flow velocity can be both lower and higher than the ground speed. The quantity itself is raised to the power of two, so it has a significant impact on the final figure.

It is important to note, that the wind direction also has a direct impact on the flow characteristics of the object (unless it has a uniform shape, like a sphere), affecting its coefficient of drag for various conditions. The difference between the direction of travel and the apparent wind direction is referred to as the yaw angle. Since both of these are vector quantities, the addition of the two and the resulting properties might not be straightforward to most.

In recent years, the design of cycling equipment has gradually evolved towards higher aerodynamic efficiency, resulting in many areas of potential drag reduction.

The first and most important consideration is the rider itself. Positioning the body in a way that better interacts with the bicycle and reduces the frontal area of the system is the single greatest way of reaching higher efficiency.

Aero bars are used on TT and triathlon bikes to enable riders into a more streamlined position, placing the arms low down and in front of the body. Ideally, the rider is then able to lower his head into the resulting gap, bringing the frontal area down even further.

The shape and size of the helmet becomes critical at this point, as it is an area of high-pressure buildup and greatly influences the airflow further downstream. The exact position of the arms in terms of stack, reach and pad width, plus the type of the helmet need to be refined using an empirical method of aerodynamic testing, as they are extremely individual.

After completing aero testing, riders often opt for custom handlebars manufactured to the specifications that have proven to be the most efficient. These handlebars form a streamlined leading edge at the rider`s forearms, cleaning up the leading edge of the bike for improved performance.

Even in an optimised position, the body of the rider is still the greatest contributor the overall drag, which means that the clothing that covers it has a significant impact. Modern skinsuits use elaborate material selections and seam placing to manipulate the flow regime around the arms, shoulders, torso and legs, contributing to the overall drag reduction. Under UCI rules, it is not allowed to implement topographic elements into the material itself, so the latest versions of high -performance skinsuits use smooth fabrics in combination with a textured base layer to achieve the same effect. A rougher texture energises the boundary layer, enabling the airflow to stay attached for longer, thus reducing the size of the low-pressure wake and thus drag. The legs and feet have a significant impact as well due to their constant cyclical motion. Removing leg hair for a smooth finish and covering the feet with flow smoothing overshoes/socks is a commonly used tactic in racing.

Aerodynamically optimised frame designs are crucial for high performance and offer a notable decrease in drag compared to traditional round tube models. It is important to note though that in terms of the whole system, the frame does not account for a very large portion of the drag, so the difference between proven high-performers of competing brands will be relatively small. The recent introduction of disc brakes has opened up a whole host of new possibilities, where the design was previously constrained by the placement of the rim brake callipers, enabling for faster bikes overall, despite the fact that the brake discs and callipers add on frontal area by themselves. The same is true for modern wheel and rim designs, where the removal of the brake track enabled designers to create more efficient, lighter and stronger rim shapes.

Aside from these main components, there are other, smaller specialty items that are often used to further refine the overall setup. Low rolling resistance is often the main aspect when choosing tires, however their shape, size and interaction with the wheels/rims can often lead to further gains. The front tire is particularly important in this regard, as it acts as a leading edge. The inflation valve on the wheels is also an area where drag is generated, so naturally there are options that allow for hiding it or covering it with an aerodynamic fairing. Small aerodynamic gain can also be implemented in the drivetrain. Aerodynamic cranks, pedals and chainrings are now widely used in TT applications. The use of aerodynamically optimized rear derailleur pulleys is often debated, however independent tests show a slight sail effect, similar to what is found on disc wheels.

Want to improve cycling CdA and efficiency? Book a consultation with us to learn about the most optimal way to become a faster athlete!